Research Experience

A view of the sunset in Waikiki, Oahu.

A view of the sunset in Waikiki, Oahu.

Overview

I am an expert in the taxonomy, systematics, and evolution of Drosophilidae (Diptera), with a focus on natural populations. I integrate field collections and taxonomy with phylogenetic inference to study Drosophilidae diversification through biogeographic patterns, evolution of morphological traits, and the formation of new species, from population divergence to clade diversification, while gaining insights on the driving forces leading their evolution.

Drosophilidae Taxonomy

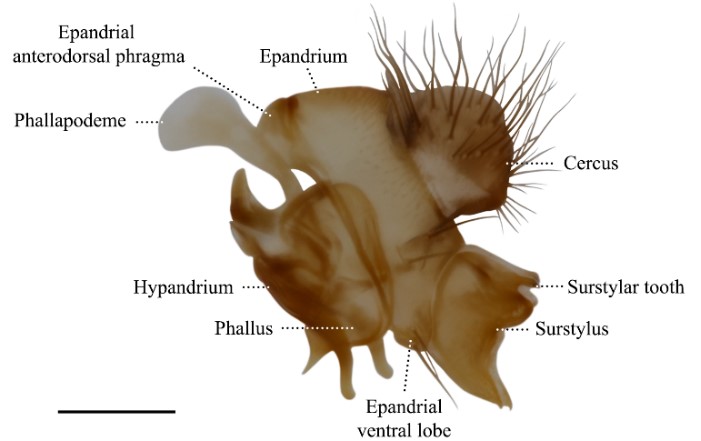

The identification and description of Drosophilidae species involves the analysis of external morphology and genital and anal segments located at the tip of the abdomen, referred to as terminalia. Before efforts to standardize the morphological terminology across Diptera were made in the 1980’s (McAlpine et al., 1981), research groups would adopt independent sets of terminologies. Since homologies were not often considered, multiple terms have been used to refer to the same characters. Recent projects revised the previous nomenclature, introduced new terms to refer to internal and external characters, and produced a visual atlas that identifies structures in the male (Rice et al., 2019) and female (McQueen et al., 2022) terminalia of Drosophila melanogaster. I expanded this initiative to encompass all the external morphology characters and terminalia of the genus Scaptomyza and prepared a visual atlas to link historical and future species descriptions (Rampasso & O’Grady, 2022b). The proposed terminology has been adopted in an identification key of the major groups of native and invasive Drosophilidae in Hawaiʻi (Rampasso & O’Grady, 2022a), in a Scaptomyza species description (Burgunder et al., 2022), and will be adopted in upcoming taxonomic revisions.

Male terminalia (Figure 1) is the most important character system in Drosophilidae taxonomy, especially in groups containing members that are indistinguishable by external morphology. Male terminalia is often used to delimit species, and is highly variable between closely related species, which indicate they evolve faster than all other morphological traits (Hosken & Stockley, 2004; Simmons, 2014). My ongoing research focuses on the subgenus Elmomyza, the largest within the genus Scaptomyza, currently containing 86 described species, all endemic to the Hawaiian Archipelago. I am describing ~10 new species, based on male terminalia analysis (Figure 1), and proposing species groups that reflect their ecological associations and morphological characters (Rampasso & O’Grady, in prep.). I have mentored one undergraduate researcher in the process of describing a new species, and we erected the first species group within the genus Scaptomyza (Burgunder et al., 2022).

Drosophilidae Speciation Driven by Ecological Associations and Geographical Isolation

Speciation in Drosophilidae is intimately linked to the associations that taxa form with various breeding and oviposition substrates, as shifts in the ecologies usually accompanies or initiates the divergence process. I collected various types of substrates (Figure 2) in a forest reserve located at the Universidade de São Paulo campus. This represents a small fragment of the Atlantic Forest, located within a concrete jungle in the middle of São Paulo (Brazil). I sampled fruits, flowers, and fleshy fungi over the course of a year. I reared over 3,000 drosophilids, belonging to 38 species across 7 genera, in addition to thousands of other insects (Rampasso, 2019). My research found that drosophilids complete their life cycle and sustain their populations within that tiny forest fragment with limited resources, instead of using it simply as a feeding site on their way to a larger and more abundant natural area (Rampasso, 2019).

I am also interested in understanding how geographic isolation might act as a driving force for the process of speciation. I obtained the prestigious “Brazil Scientific Mobility Program” scholarship to support my research, and examined populations of Drosophila arizonae, distributed throughout the southwestern United States into southern Mexico (Figure 3). My prediction was that geographically isolated populations would present concordant patterns of genetic (mtCOI) and morphological (phallus shape) differentiation across the broad, disjunct range of this species. Our results suggest that the Tuxtla Gutiérrez (Chiapas, Mexico) population may be in the early stages of lineage divergence. This was the only population collected to the south of two important geographic barriers, the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, both of which have been associated to reduced gene flow among other organisms (Rampasso et al., 2017).

Inference of Evolutionary Patterns through Phylogenies

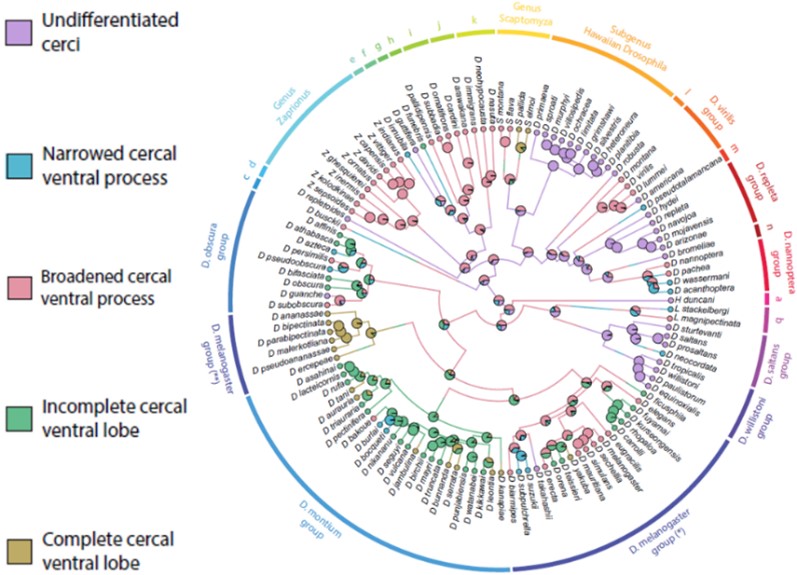

I used a recently published phylogeny based on 155 whole genomes (Suvorov et al., 2022) to investigate the evolutionary patterns that drove the impressive morphological variation in Drosophilidae male terminalia (Figure 4). I analyzed two periphallic structures responsible for grasping the female terminalia and securing a tight genital coupling. I proposed categories to describe the main patterns of morphological variation of two periphallic structures, reconstructed their states in the ancestor of the family, and inferred how these structures diversified across multiple genera and species groups (Figure 4). Our results provided insights into the association between those characters and their possible role in copulation (Rampasso & O’Grady, submitted).

Although the Suvorov et al. (2022) phylogeny provides insight into the evolution of 155 taxa, this only represents a fraction of the ~4,400 described species of Drosophilidae. The Petrov Lab at Stanford University established partnerships with multiple research groups across the world to expand their initial effort and reconstruct a broader whole genome phylogeny to the family, with thousands of taxa. The O’Grady Lab is part of the project, and I am a collaborator. I have helped to supply over 900 Drosophilidae strains, including Scaptomyza species, from the National Drosophila Species Stock Center, the O’Grady Lab ethanol collection, and personal collections.

The genus Scaptomyza contains 274 described species, distributed on all continents (except Antarctica) and many remote oceanic islands. Two recent studies supported different hypotheses for the pattern of origin and diversification of the genus. (Lapoint et al. (2013) proposes that Scaptomyza originated and diversified in Hawaii, and then dispersed elsewhere. Katoh et al. (2017) suggests they originated on a continental landmass and then migrated to Hawaiʻi in multiple colonization events. However, the low support of relationships in some areas of both phylogenetic reconstructions indicate that additional sampling is necessary. I will use whole genomes, currently being sequenced by the Petrov Lab, to reconstruct a phylogeny with better resolution in poorly supported clades and test which hypothesis is more likely to describe their pattern of origin and diversification (Rampasso & O’Grady, in prep.).